|

A

conversation with

Jock Winkworth

by Norman

Whitwood in 1982

From the Border Country to British Aerospace;

from apprentice draper to aircraft inspection superintendent.

After forty-five years in the aircraft

industry, most of them in the hot-seat of inspection, Jock Winkworth

obviously prefers to talk about those early days in the tiny

Scottish village of Eaglesfield, Dumfriesshire.

"In the drapers and grocers shop where I

served my apprenticeship", he says, "you had to be prepared to sell

anything from a sack of corn to a suit. I started on eight shillings

a week and we worked a basic fifty four hours".

His employers also owned a sheep farm and Jock

continually returns to the subject. They had to work on the farm for

two weeks every year, shepherding, branding and even shearing the

flock. He obviously loved every minute of it. "Everyone worked on

the farms in six month terms, so the shop rendered accounts in May

and November, just as they were all getting paid off".

Jock used to go back regularly, but when he

returned this year for his son's marriage to a Glasgow girl, it was

the first visit for a long time. With the young couple setting up

home in Carlisle, the nearest large town to his home village, Jock's

migration has turned full cycle. Having just retired, he hopes to go

back more often. His irrepressible, dry sense of humour is never far

from the surface. "I've still got two houses up there, both with

tenants. I only charge them five bob a week, but they refuse to die

so I can get in and change the places. Very inconsiderate, really!".

He left Scotland when he was twenty, in 1937,

and moved to Short Brothers and Harland in Belfast as an aircraft

fitter working on Bristols and Handley Pages. "Some of the aircraft

didn't have much bottle" he says, "but they had to make something".

Having left Eaglesfield because of lack of prospects, this was a

completely new world, in more ways than one. "I had to sneak off to

the toilets to sort out Decimals. We never did them at school".

Jock worked on the same bench with an

Australian, a Welshman and an Irishman and with the shipyard next

door, his lifelong career in the hard, but friendly, world of

engineering had begun. By the time of Jock's retirement, aircraft

construction and testing techniques, as well as metals

technology, was to reach incredible levels of sophistication, but in

the early days in Belfast you just drew some sheets out

of store and slapped them on the aircraft - no heat-treatment, no

age-hardening, nothing.

Jock remained in Belfast for three years

before moving to Luton after four years in Reading and two years as

an RAF flight mechanic. In 1947, ten years after leaving home, he

returned to Scotland, only to head south again after three months

because "I couldn't stand it".

When he did journey south again it was to DeHavillands at Hatfield, where he was to remain for thirty five

years. "I was always an inspector" says Jock. "In those days we were

selling Comets to just about everyone at half a million each. If

we'd had Green Shield Stamps, we'd have given them away too".

DeHavillands became Hawker Siddeley and then British Aerospace but

for Jock nothing changed much. They just kept on making aeroplanes

and the names rolling off his tongue, sounding like a roll call of

British post war aircraft classics: Mosquitoes, Venoms, Vampires,

Chipmonks and many others.

Besides an increasingly well-established

career, Jock made another valuable find at Hatfield: his wife Peggy.

Peggy was secretary to the Financial Director and Jock was in digs

with her sister. "Her hair is no longer red, but it was in those

days" says Jock, "I must have been mad!".

Mad or not, since they moved to Harpenden in

1955, they have raised a super family of three strapping boys, all

of whom have done very well for themselves under their parents'

canny guidance. Jeremy the eldest has his BSc. and he's married and

living in Michigan, USA. Kevin is the next one, with a degree in law.

He's the one just married and living in Carlisle and then there's

Andy, who decided he wanted to be a policeman. Educationally, Jock

had his own incentive scheme. It was five Bob for an '0' level and

fifty quid for a degree", he says. It seems to have worked because

together with the two degrees, they all have ten '0' levels each.

The boys have been totally absorbed in Jock's

hobby of rebuilding Morris 1000 motor cars. "It all started when

Jeremy needed a car to learn to drive. I bought a Morris 1000 for

him and we renovated it and the others followed suit. Altogether,

we've had about twenty through our hands". The lads all passed their

tests first time, too. Mind you, I used to take them all down to the

test centre and we would follow the people being tested. Then I'd

say "There you go. Easy, isn't it?"

That kind of direct thoroughness and humour is typical of Jock and

these are invaluable characteristics which have clearly been passed

on to his sons. Now that he has retired, he is looking forward to

simply pottering and enjoying life. He grows a vast array of

vegetables in his garden, utilising every square inch, and will turn

his hand to any odd jobs for themselves and their friends. "I've

always worked on wood and metal, always worked on the house" he

says. " If you can't knock a nail in mate, you're helpless."

Jock is the kind of person who is known by

everyone, even in a place as large as British Aerospace. An often

irascible, but always knowledgeable factory floor character with a

heart of gold; the one who looked after the apprentices and trained

the young inspectors; the almost institutionalised old boy who was

always ready for a chat and a laugh, ready to perform any favour in

return for goodwill and friendship.

He will be missed every bit as much as he in

turn will miss the hassle and argument which is so much a part of an

Inspector's life. Perhaps because his retirement is very recent,

Jock still seems reluctant to talk about his former job .

"It wasn't always easy" he says. "There was a lot of troubleshooting

and we were always up against Production. They naturally want stuff

out the door, but it's your inspection stamp that goes on it. Once

you stamp it, you're on your own. If you don't stamp it, they can't

take it."

Whatever life now has in store for him, Jock

will still have his favourite excuse when things do not go according

to plan. He will be remembered long after his departure, standing

with hands held up and an innocent expression on his face, pleading

in that distinctive Border Country accent, "I don't know everything

you know, I'm only a draper's assistant."

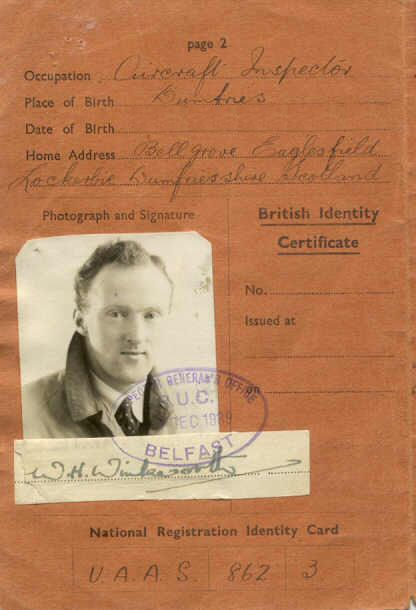

Jock in September 1939 - WWII Travel Card

Return to the Main Menu

Page

|